In part one of this series, we took a look at the bloody history of the House de Bellême from William I de Bellême through William Talvas, who was deposed by his son Arnulf after alienating the House of Giroie. This post will take the story of the family through the story of their resurgence and the Norman Conquest of England, which made them into a truly powerful family – at least for some time.

We left off the narrative with William Talvas’s deposition by his son Arnulf and his expulsion from his former lands. For several years, William Talvas wandered about Normandy, until he reached the castle of Roger de Montgomery, one of the foremost Norman magnates. Roger took William in, and made him an offer he couldn’t refuse.

Roger de Montgomery Gets a Bargain

But first, let’s take a moment to explore just who Roger de Montgomery was. Roger was the scion of a powerful and well-established Norman family, who had traditionally been the holders of the vicomte (viscountcy) of the Hiémois, along the turbulent border between Normandy and the County of Maine. Once the young Duke William II of Normandy (later to known as William the Conqueror) reached his age of majority, Roger became his close companion and indispensable right hand.

In the past, Roger had been an adversary of William Talvas, as the Bellêmes would occasionally launch raids into the Hiémois and were more generally a destabilizing factor along the Norman frontier. But now that Talvas was dispossessed, Roger de Montgomery was quick to spot a new opportunity for aggrandizement.

Roger reached an agreement with William Talvas, who granted him the hand of his daughter Mabel in marriage. In exchange, Roger de Montgomery would work to retake the lands formerly held by William Talvas (now held by his treacherous son Arnulf) and give those lands to his wife, Mabel de Bellême. This was a win-win situation – so far as William Talvas was concerned, he had acquired a powerful ally to help take back his lands for his daughter. Meanwhile, it was also an excellent long-term play on Roger’s part, as any lands held by Mabel would eventually, with her death, transfer to their shared children.

As mutually beneficial as this pact between Roger and William was, though, there were still numerous hurdles left to clear. The castles which had been held by Talvas – Domfront and Alencon – were some of the most formidable in all of Northern France. The castle at Domfront, in particular, was situated on a rocky promontory overlooking the village, and was nearly impossible to take by storm. As matters stood, there was no realistic way Roger de Montgomery would be able to reclaim the castles for his wife. Fortunately for him, however, developing political events would work in his favor and bring him a powerful new ally.

Arnulf’s Fate

But before we discuss that, we need to go back and look at how things were developing in William Talvas’s old lands. The last we knew, William Talvas’s son Arnulf was lord. However, Arnulf de Bellême didn’t last very long in his usurped position. Orderic Vitalis tells us the story of how, one day, Arnulf and a bunch of his thugs were on the road, when they came across a nun and her pet pig (and yes, the story does indeed indicate that this pig was a pet, rather than a commodity).

Naturally, Arnulf and his cronies demanded the pig. The nun begged and pleaded to be able to keep her pig, but Arnulf paid her no heed, and he had his men butcher the pig right in front of the wailing nun. That evening, the men gorged themselves on the stolen pig, but Arnulf apparently engorged himself too much. In the morning, it was discovered that Arnulf de Bellême had suffocated to death in his sleep.

Presumably, the castles of Domfront and Alencon returned to Yves de Bellême, Bishop of Sées, after Arnulf’s death. You’ll recall how we wrote back in the first part of this series how he was the rightful holder of the castles. However, shortly after Arnulf’s death the entire political situation in the County of Maine exploded, with far-reaching consequences for the Bellême estates.

Geoffrey Martel’s Seizure of Maine

For over half a century prior to the events we’re discussing, Northern France’s geopolitics had been defined by an ongoing feud between the Counts of Anjou and Blois. All of the more minor principalities in the region, including the County of Maine, were drawn into the conflict. The Counts of Maine tended to side with the Blésois against the Angevins, as the expansionist Counts of Anjou posed a more immediate threat to their interests.

However, some of the most powerful Mayennois nobility, who naturally engaged in a struggle with the Counts of Maine for control over the county, sided with the Angevins, whom they saw as a useful counter to the Counts of Maine. Foremost among these pro-Angevin nobles were the members of the House of Bellême, including the lord of Bellême and Bishop of Sées, Yves de Bellême.

In 1051, Count Hugh IV of Maine died, leaving behind a young son, now Count Herbert II. Geoffrey Martel took advantage of the weakness of the County of Maine and he marched in and occupied the county, effectively taking the young count hostage. Martel also occupied several key castles throughout Maine in order to solidify his grasp on the county, and critically, he also occupied the castles of Domfront and Alencon.

This was unacceptable to Duke William. Anjou was emerging as a serious threat to Normandy’s south, and Geoffrey Martel’s control of these critical strongholds on his frontier was a significant threat to the tenuous stability of the Hiémois. Although William didn’t have the power to oust Martel from the County of Maine itself, he had little choice but to seize the border castles of Domfront and Alencon. Thus, you had a complete convergence of interests with regards to the castles: William wanted them removed from the hold of Geoffrey Martel, while Robert de Montgomery – a staunch supporter of William’s – wanted those castles for his wife. And so, in 1051, Duke William of Normandy marched on the stronghold of Domfront.

Siege of Domfront and Alencon

As we’ve mentioned above, both Domfront and Alencon were well-defended and extremely difficult castles to besiege. Domfront, in particular, was considered to be impregnable, surrounded as it was on three sides by a rocky escarpment. Duke William had no choice but to starve the garrison out, and accordingly, he constructed several small siege castles around the castle, cutting off their supply lines.

The Normans settled in for a long siege, with William and the other Norman nobility amusing themselves with frequent hunts and diversions. However, Geoffrey Martel was unwilling to allow William to just snatch up the castle without any effective resistance on his part. He assembled a force and marched north to Domfront, hoping to cow William into breaking off the siege.

As a general rule, medieval nobles shied away from fighting pitched battles, preferring to raid and besiege instead. Pitched battles were insanely risky, killed off extremely large amounts of labor and fighting capacity, and could completely devastate a dynasty in the span of a few hours. Accordingly, Geoffrey Martel had every reason to assume that William would pull back once he showed up with an army at his back.

William, however, did no such thing. He called Geoffrey Martel’s bluff and drew up his own forces for battle. Now it was Anjou who faced the dilemma: fight or withdraw? He was just as cognizant as anyone else of the risks of a pitched battle, and Domfront and Alencon were ultimately far-flung outposts of his power, not necessarily worth a bloody battle. In the end, Anjou blinked, and he withdrew with his forces southward. Domfront’s defenders were left on their own.

A less ambitious man than William might have contented himself with this victory. He had faced down one of the most powerful warlords in Northern France and came out on top. All he needed to do now was to sit tight on his siege fortifications and wait for the defenders to run out of food. But William was not that sort of man. He was a man of action, and he saw an opportunity to take advantage of Geoffrey Martel’s withdrawal.

What happened was that William had been made aware that, while Domfront was well-defended, Alencon was not expecting an attack and could be easily taken. Now that Geoffrey and his army were gone, there would be no effective way for Alencon to resist him.

Leaving a token force behind him to maintain the siege of Domfront, William rode through the night with the bulk of his men, arriving at Alencon at dawn. A group of townspeople, defending an outlying fortification, began to mock William, beating animal skins on the walls of their fortification to insinuate that he was a descendant of lowly tanners, and mocking the common birth of William’s mother. And let me give you a little tip – when you come across a guy like Duke William, you don’t insult his mother. Enraged by the taunting, William and his knights took the fortification by storm, put it to the torch, and chopped off the hands and feet of all 32 of its surviving defenders.

Frightened by this display of savagery, the men of Alencon surrendered that very day. William rode back to Domfront with the good news, and when they heard that the city of Alencon had been taken in a day, the demoralized defenders of Domfront also agreed to surrender their castle to William. Thus, in one swift and brilliant stroke, William had secured both the city of Alencon as well as the nearly impregnable castle at Domfront. It was a brilliant coup for William, but more importantly for our story, it made Roger de Montgomery and Mabel de Bellême a powerful couple indeed.

To England!

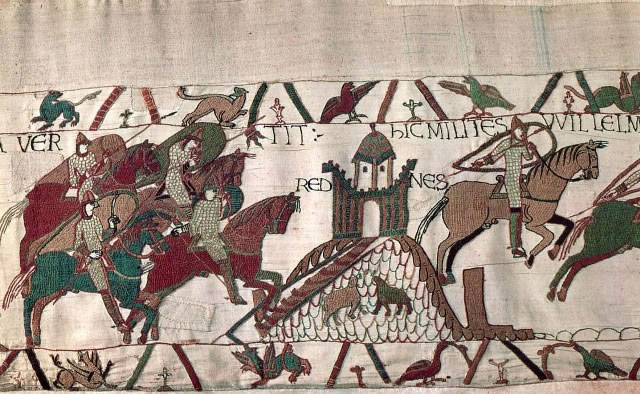

The fifteen years following the capture of Domfront and Alencon were good years of expansion for Roger and Mabel. Roger was one of Duke William’s closest confidantes, and he and his wife steadily leveraged their influence with the Duke to expand their holdings and push rivals out of the way. However, the yields gained during those years paled in comparison with what followed in 1066, when Duke William of Normandy conquered the Kingdom of England and entered the pages of history as William the Conqueror.

It’s not clear whether Roger de Montgomery actually fought alongside William at the fateful Battle of Hastings or not (there are some sources that maintain that he remained behind to attend to Normandy in William’s absence), but what we do know is that the Norman Conquest allowed Roger to cash in on the decades of goodwill he had built up with the Duke.

Roger de Montgomery received vast estates in the newly conquered kingdom. He was granted the Rape of Arundel (a strategically located subdivision of the County of Sussex) and the Earldom of Shrewsbury. In this latter role, he was expected to defend against the Welsh and, if practicable, to expand into their lands. In addition to the above two grants, Roger de Montgomery was granted hundreds of manors spread across the entirety of Southern England, from which thousands of pounds flowed into his coffers every year.

Roger was now at the pinnacle of his power, holding vast estates on both sides of the English Channel. The only question that remained was, would he be able to hold onto them?

To be continued in part three…

Bibliography

David Bates, Normandy Before 1066. New York: Longman Group, 1982.

Gesta Normanorum Ducum of William of Jumièges, Orderic Vitalis, and Robert of Torigni, ed. and trans. Elisabeth M. C. van Houts, 2 vols. OMT (Oxford, 1992-5).

Kathleen Thompson, ‘Family and influence to the south of Normandy in the eleventh century: the lordship of Bellême’, in Journal of Medieval History, 11:3, pp. 215-226.

Geoffrey White, ‘The First House of Belleme’, in Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Vol 22 (1940), pp. 67-99.