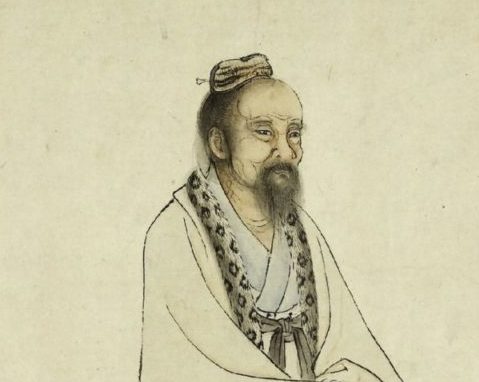

Recently, I’ve gotten very interested in reading old Chinese literature, particularly Taoist philosophy. In this blog post, I’m just going to leave you with one of my favorite anecdotes from one of my favorite Chinese authors, Chuang Tzu (c. 360 BC). Sometimes, what we think is clever is really self-destructive, and what we think is mulish stupidity is ultimately self-preservation.

“Carpenter Shih went to Ch’i and, when he got to Crooked Shaft, he saw a serrate oak standing by the village shrine. It was broad enough to shelter several thousand oxen and measured a hundred spans around, towering above the hills. The lowest branches were eighty feet from the ground, and a dozen or so of them could have been made into boats. There were so many sightseers that the place looked like a fair, but the carpenter didn’t even glance around and went on his way without stopping.

His apprentice stood staring for a long time and then ran after Carpenter Shih and said, “Since I first took up my ax and followed you, Master, I have never seen timber as beautiful as this. But you don’t even bother to look, and go right on without stopping. Why is that?”

“Forget it—say no more!” said the carpenter. “It’s a worthless tree! Make boats out of it and they’d sink; make coffins and they’d rot in no time; make vessels and they’d break at once. Use it for doors and it would sweat sap like pine; use it for posts and the worms would eat them up. It’s not a timber tree—there’s nothing it can be used for. That’s how it got to be that old!”

After Carpenter Shih had returned home, the oak tree appeared to him in a dream and said, “What are you comparing me with? Are you comparing me with those useful trees? The cherry apple, the pear, the orange, the citron, the rest of those fructiferous trees and shrubs—as soon as their fruit is ripe, they are torn apart and subjected to abuse. Their big limbs are broken off, their little limbs are yanked around. Their utility makes life miserable for them, and so they don’t get to finish out the years Heaven gave them, but are cut off in mid-journey. They bring it on themselves—the pulling and tearing of the common mob. And it’s the same way with all other things.

“As for me, I’ve been trying a long time to be of no use, and though I almost died, I’ve finally got it. This is of great use to me. If I had been of some use, would I ever have grown this large? Moreover, you and I are both of us things. What’s the point of this—things condemning things? You, a worthless man about to die—how do you know I’m a worthless tree?”

Source:

Chuang Tzu: Basic Writings (trans. by Burton Watson). New York: Columbia University Press (1996), pp. 59-61.

1 Comment